Amir Hassan Cheheltan says he has gotten used to the fact that nobody is completely safe in Iran.

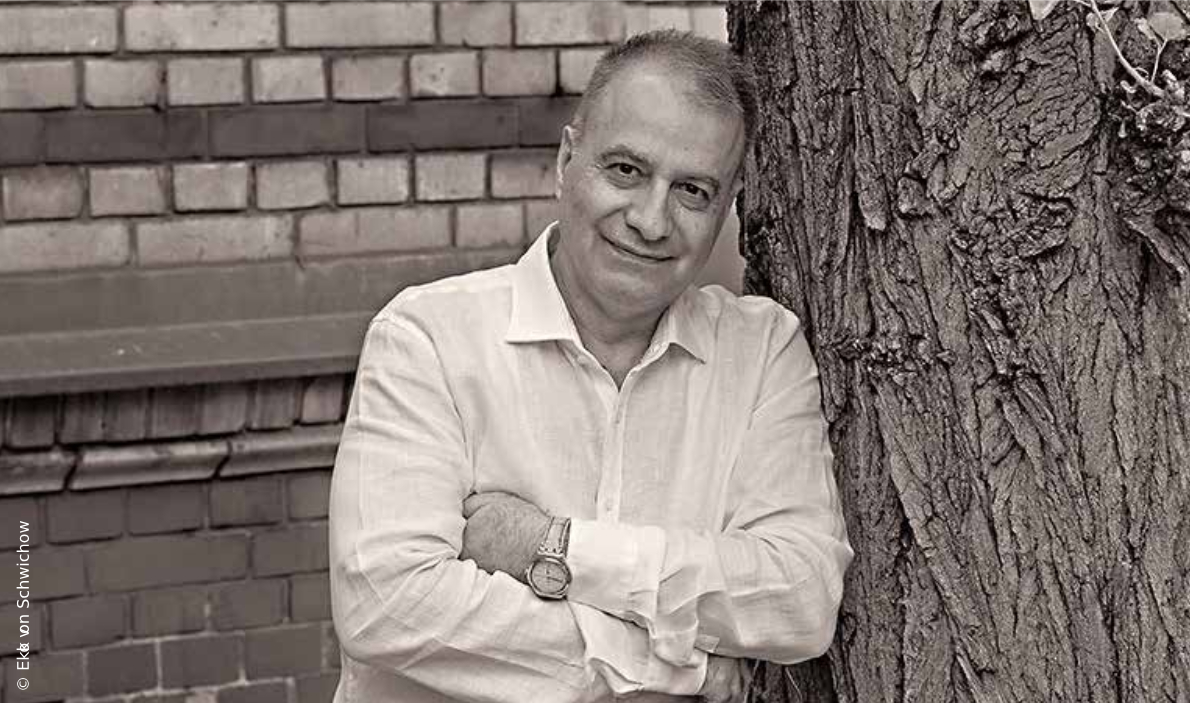

Amir Hassan Cheheltan is a stocky, lively man. He receives visitors on a sunny autumn day in an apartment overlooking Lake Zurich. The idyllic surroundings contrast sharply with his location in the Middle East.

Cheheltan is touring Europe with his new novel, "The Rose of Nishapur," and also appeared at the "Zurich Reads" literature festival. The setting for his books is usually Tehran, where he was born in 1956 and still lives with his family. He only left his homeland for his studies in Great Britain and other stays abroad; he also served in the First Gulf War.

In the conversation, conducted in English, Cheheltan is clearly striving to present a positive image of Iran and dispel the clichés. Like an ambassador of Persian culture, he raves about Tehran. When he talks about his homeland, his eyes light up, and his high-pitched voice sounds even more melodious than usual.

- Mr. Cheheltan, in response to Iran's massive attack on October 1st with around 200 ballistic missiles, Israel recently attacked targets in Iran, and the regime is threatening retaliation. What is the mood in Tehran?

Perfectly normal, everyday life goes on.

- Aren't people afraid of an open war with Israel?

Yes, very much so. But fear doesn't paralyze daily life. We waited a long time for the Israeli retaliatory strike. Fortunately, it wasn't a major attack. And the Iranian government initially reacted quite calmly, which relieved me.

- According to media reports, Iran is now planning a fierce retaliatory strike. That would be a big mistake. I hope the Iranian government reconsiders its decision. Is she that sensible?

I am very critical of her; the ping-pong between the two countries must finally stop.

- Some Iranians, however, hope that a conflict will bring down the regime. What is your opinion on this? That's a very naive, if not downright stupid, idea. An overthrow of the government orchestrated by Israel and the US would be very problematic. Even if it came to that, what would be the next step?

Two years ago, there were massive protests after 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, arrested for "indecent clothing," died in the custody of the morality police. Recently, images circulated worldwide of a young woman who, in protest, stripped down to her underwear in the street.

- Does the "Woman, Life, Freedom" movement still exist?

Such protests are not isolated incidents. Even though the movement is no longer as large as it once was, one notices in everyday life that it has had an impact.

- For example?

Today you see more and more women without hijabs, but it depends on the city and even the neighborhood. In northern Tehran, for example, I see many women without hijabs. The morality police there usually leave them alone.

- Even back then, some hoped for a new revolution. Is that now out of reach?

Yes, thankfully. Wasn't the one in 1979 enough? A revolution won't solve our problems. I don't like revolutions.

- Why not? They are suffering under the regime too.

Revolutions are very costly. Our country already had one forced upon it by the Shah regime because we needed to get rid of it. But the Shah, with his policies of suppression, had paved the way for the mullahs' repression. I am in favor of reforms. Because a revolution destroys everything in order to build something new, the nature of which is unknown. For a revolution to succeed, civil society would first have to mature.

- As a young man, you had to flee abroad to escape the mullah regime. Why?

In the 1990s, I was very active in re-establishing the Iranian Writers' Union. The government didn't like that. So my colleagues and I were persecuted and terrorized. My name appeared on many blacklists, death lists that were published from time to time. I also survived an assassination attempt. When I was on a bus to Armenia with twenty other writers, the driver jumped out of the moving bus to send it careening down a slope. Luckily, a passenger grabbed the brakes in time.

- Do you feel safe now? After all, you're saying things that the Iranian government probably won't like.

No. But I've grown accustomed to the fact that no one is completely safe in Iran. And everyone who lives there and works as a writer, artist, journalist, lawyer, or activist is always taking a risk. Personally, I'm still able to overcome my fears, and as long as that's the case, I'll stay in Iran.

- Your new novel, "The Rose of Nishapur," is about a love triangle in Tehran, including a homosexual relationship. In Iran, all of this has to happen in secret. Is it really possible to live so freely there?

Yes, contrary to the many clichés about Iranians in the West. While it's true that women are repeatedly beaten or arrested for dressing or wearing makeup as they please, and that people are executed, there isn't only this Iran. Most people resist the regime and live as they choose. Tehran, in particular, demonstrates this: it's a megacity with more than 15 million inhabitants and a city of rebellion against all things authoritarian. My novel tells the story of young people in Tehran who also drink alcohol and party in hidden nightclubs.

- Is this secret parallel world in Iran one reason why people still have hope for change?

Exactly, because Iranians know what freedom can feel like. Add to that their history of persistent oppression; it has always taken resistance to survive. And all we can do is hope that things finally change. That the hardliners stop ruling the country. That inflation, corruption, and unemployment are tackled. That the censorship ends.

- Her books have been banned in Iran for over twenty years. What is the government's objection to her novels?

It deals with, among other things, eroticism and politics. And since I can't imagine a work of fiction without these two elements, I no longer even submit my novels to the censors, but have them published and printed abroad, in other languages. It's painful for me that my books can't be read in my home country. But that wasn't my decision. They want to silence me.

Carlo Mariani

November 13, 2024

5 min